Still chasing the Moody mystery

Last updated 4/8/2009 at Noon

A famous author living in Waco named Robert Fulghum once said, “Myth is more potent than history.” Myths seem to hold a popularity among our culture and give us the themes that grow into ‘local color’ and ‘southern flair.”

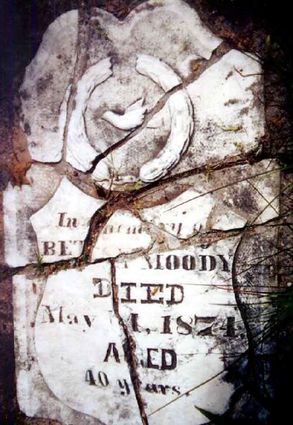

One such myth that has been passed through the generations of Orange County is the solitary grave that rested seemingly alone in a field. The name on the cracked sandstone marker encased in long-worn concrete is Betsy Moody. Below the name is a recorded date of death - May 14, 1874. The line that follows is part of the mystery.

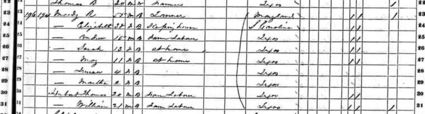

Many have thought and heard through rumor that this was a child that died at the tender age of 10. Upon further research, that seems to be only a beautiful and tragic fable. In the 1870 Orange County census, a Moody family was mentioned living near the grave site located behind the Entergy plant near what is now part of Bridgefield Estates. The homestead was a permanent one and said to be land that had been owned by the Winfree family.

These records have shown that Elizabeth ‘Betsy’ Moody was in fact the 38 year old mother of 5 children. She was a native of South Carolina and the wife of Maryland born Robert Moody. His profession was listed as farmer and there were two farmhands, Thomas and William Hubert, mentioned on the census report.

Betsy’s occupation was listed as ‘Keeping House’, and it is stated that she had no formal education. Her race was categorized as black, and like many rural inhabitants at that time, she could not read or write. Her children were listed as being born in Texas. Andrew, 15; Sarah, 13; May, 11; Lensan, 4; and Martha, 2.

Vaccines and immunizations came later, so disease took the majority of children before they reached adulthood. With the variety of infections and illnesses, it was not uncommong for a death certificate to read “griping in the gut,” which was dysentery, or simply “fever.”

Had Robert and Betsy been emancipated slaves, the European name, “Moody”, might well have been the name of the family they once “belonged” to. Although census records are the most useful tool in finding information from that time period, there is no solid proof of the origins of this family. In a report from 1880, Robert’s father was listed as being born in Virginia. It is unclear whether he also carried the Moody name.

The grave marker was made of delicately carved sandstone which is not native to this area. This item would have certainly been expensive at the time, and a couple of theories exist about why this grave was the only one in that place to be marked.

Local history and cemetery buff, Oliver Peasley, thinks, “Either her husband had earned enough through his life to afford a headstone or the people she worked with thought highly enough of her to get one.” At the time of her death, such stones had to be ordered, chiseled and delivered from far away. This process could take as long as a year or two and the family would have to remain in the area for placement of the stone. This leads some residents to believe that the Moody family intended to keep roots in the Orange County area.

Peasley believes that this grave site was a complete cemetery that contained up to six more graves although the additional sites were unmarked. Also, he thinks that this property was land that held former slave quarters and the emancipated slaves stayed to be sharecroppers on familiar land.

According to Peasley’s research, the site was a slave cemetery and in the early 1800s was called Hollywood Cemetery. “It seemed to be a popular name among slave and black cemeteries of the time. They liked the name Hollywood and would name more than one place the same thing.” says Peasley.

Sadly, recent reports have stated that the headstone is no longer in the grassy area near Windham Road north of Bridge City. The assistant to Gina Mannino at the Bridge City curriculum office, Donna Riley, said “It is very upsetting to the neighborhood that the marker is gone.” It seems that this well-known site was cared for by many families, including the Rileys, that live nearby.

No sources have been found that know the current location of the gravestone.

Donna and her husband took the time to do maintenance and upkeep on the site, and Donna even had a habit of refreshing the flowers. Though now broken and barely readable, the condition of the sandstone marker was thoughtfully preserved by an unknown party in the recent past. At some point in the history of Orange County, the fragile headstone of Betsy was placed, piece by piece, into concrete to keep all of the parts together. Oliver Peasley had been to the cemetery when the encasement was still intact. However, encroaching construction seems to have been a factor that caused cement holding the marker to also be damaged and cracked in approximately late 2000.

Cetha Haure, the retired secretary of Bridge City High School, knew the story of Betsy Moody very well.

Her husband Johnny had come across the solitary site many years ago while hunting and riding horses with friends.

Johnny related through his wife, “It was hard to find if you did not know where to look.

A long time ago it was just an old marker in the woods.” Haure had grown up near the Turner Road region and said that before the land was developed and logged it was difficult to find again.

There are many reports that several different fences had been erected to protect this area.

Photos exist of a welded metal structure in the summer of 1999, but as of 2001, it had been removed.

Impending residential development left the marker alone once again.

Some Orange Countians do mention a controversy over the placement of the marker.

Craig Turner of Bridge City came across the grave while riding horses.

He said, “I had known about it from years earlier, from the stories that people would tell.

You know, there used to be a lot more graves there.” He was a bit surprised to find out that the myth of the ‘little slave girl’ appears to be false, but still spoke about the grave with compassion.

Not all locals have been as respectful of these burial grounds.

“In the late 60s, some teenage boys had taken the marker.

It was a prank, and I don’t want to mention names, but they didn’t put it back in the exact right place.” Apparently this controversy is still a whisper among residents and historians.

Oliver Peasley agreed that there was some question about whether the marker had been correctly placed.

He said, “I had intended to take a probe to check for ground that had been disturbed.” Unfortunately, due to the lengthy illness and subsequent death of his father, Peasley had never returned to the cemetery to investigate further.

Craig Turner reports, “I went out and checked after work, and it is definitely not there. Neville Thomas used to own that property, and you could see the white of the marker in the grass even from the swimming pool in his yard. Now it’s just gone and that is so sad.”

Turner thought that the current address of the property where the gravestone should be is 5325 Windham Circle. He and many other residents feel that the grave was almost a local legend. “You’d tell people about it, and then you would have to take them out there to see it.”

Though not widely publicized in the past, this site seems to have held a long-standing fascination among the community.

No records have been found that tell of Betsy’s life. Births and deaths were often written in family Bibles to be passed from generation to generation as one of the earliest forms of the genealogical family tree. There is little known about modern day relatives of this particular Moody family though some clues do exist on the whereabouts of Betsy’s family after her death. In June of 1880, a census lists Robert Moody, Elizabeth Moody, 14 and Martha Moody, 11. The Elizabeth Moody listed there appears to coincide with the age range of the Lensan Moody from the 1870 information. It is a possibility that Lensan was a family nickname for a daughter who was named after the mother - Elizabeth.

There are no further records of May Moody.

The eldest son, Andrew, remained below the census radar until 1900. Records show that he married a woman named Matildie in 1883. Though information is sketchy, 5 children were accredited to this family. At the time of the record, only two of those children were listed as living in Andrew’s home - Mattie, 12; Earnest, 11. As head of household, he rented farmland, had attended school and could both read and write. Data for the other family members remains lost, but a listing of area deaths shows that Andrew died in August of 1941 at the age of 88.

The most extensive reports surround Betsy Moody’s oldest daughter, Sarah.

She appears to have been missing from the 1880 census, but only because her name had been changed due to marriage.

In May of 1877, at the age of 20, she married Alexander Henderson.

The county of marriage was listed as Orange in the publication entitled Texas Marriages, 1814-1909.

No information was uncovered on her life with Alex or whether they had children.

However, a population schedule from 1930 showed a Sarah Henderson from the correct age range to coincide with Betsy Moody’s daughter.

She lived in Waller County, Texas.

She was a wage earning worker, at the age of 65, that was a cook for a private family.

The information listed her as widowed and no children are attributed to her married life.

Sarah did rent her home, but she never learned to read or write and was never formally educated.

The roots of Betsy Moody ran deep and grew strong in the Orange area and even spanned out to counties northwest of Houston.

Chances are that the whole story will never be known. What is known is that the family lived here in the 1870s and 1880s. Betsy died near the age of 40 - a wife, a mother and a woman loved by generations that cross the gaps of race and social stature.

“It is so sad that things like this happen to graves.” says Turner. According to the Texas Health and Safety Code, “Owner of property on which an unknown cemetery is discovered or on which an abandoned cemetery is located may not construct improvements on the property in a manner that would further disturb the cemetery until the human remains interred in the cemetery are removed...” “It’s happened to so many cemeteries. The graves are unmarked or the markers are damaged and bulldozer operators just can’t see them until it is too late” says Peasley.

In an effort to preserve small and abandoned grave sites such as this one, Texas has established an Adopt-A-Cemetery program. Through aid of non-government volunteers, nearly 70 cemeteries across the state have been helped. Details on this program can be found at http://www.historictexas.net/cemeteries/1a/adopt.htm.

Reader Comments(0)